ARCHIPENKO

and the Italian Avant Garde

Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London

4 May – 4 September 2022

Over the course of the past two decades, the Estorick Collection’s

exhibition programme has explored the various relationships between

Italian art and that of other nations, such as that which existed between

Futurism and British Vorticism. However, the present exhibition goes

a step further, as the relationship between Archipenko’s imagery and

Italian art went both ways.

The influence of Futurism on Archipenko’s work is undeniable,

but so too is the reciprocal influence of his own work on Italian artists

– particularly those who were working in the climate of the inter-war

‘return to order’, who were keen avoid the trappings of a ‘new’ traditionalism

without lapsing into an outmoded fragmentation of form,

and for whom Archipenko’s fluid, biomorphic forms represented

something of a solution to this conundrum. The exhibition aims to

highlight some of these relationships, ranging from striking Futurist

correlations to more subtle echoes discernable in the work of artists

such as Amedeo Modigliani.

The exhibition offers another important link with our own collection

insofar as Eric Estorick met Archipenko through the dealer

Klaus Perls in the late 1950s and went on to handle a number of important

works by the artist. The Estoricks exhibited his work at the

Grosvenor Gallery on various occasions, hoping ultimately to organize

a large show, and in 1961 presented a solo exhibition at their Gallery

comprising 20 sculptures and five ‘sculpto-paintings’.

This exhibition would not have been possible without the enthusiasm

and dedication of many people; I would like first to thank Matthew

Stephenson for suggesting this project, and for his constant support

throughout the process of its realization. The Estorick Collection is

naturally extremely grateful to all the lenders for their great generosity,

including The Archipenko Foundation in New York; particular

thanks go to Frances Archipenko Gray, who has been enthusiastic

about the show from the very beginning. I am also indebted to Maria

Elena Versari, the exhibition’s curator, whose great knowledge of her

subject has made this exhibition and catalogue so compelling. Finally,

I would like to thank Christopher Adams for his unflagging support

and help throughout this project, as well as my colleagues Luke Alder

and Claudia Zanardi.

Roberta Cremoncini

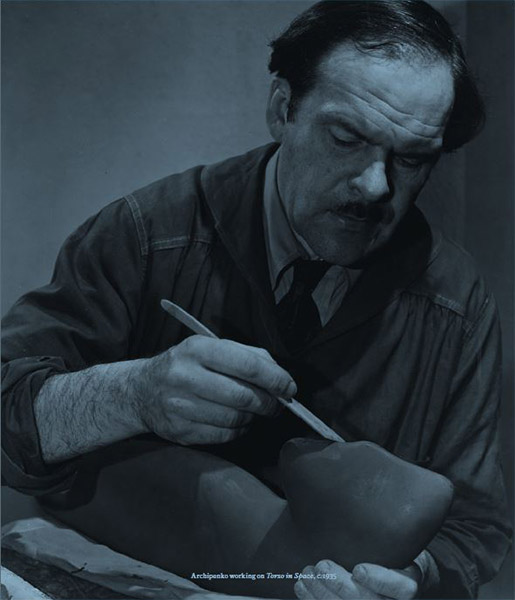

Alexander Archipenko was born in 1887 in Kiev, Ukraine. After a brief

sojourn in Moscow, he moved to Paris at the beginning of the 20th

century, where he found himself working alongside a group of other

young sculptors who were all trying to escape the imposing - and suffocating

- shadow of Auguste Rodin. Many years later, he talked about

his disdain for Rodin’s work, and in doing so revealed something of

what he himself was looking for in those early years. Rodin’s sculptures

reminded him of the curved and contorted casts of humans from Pompeii,

forms shaped by the voids of missing bodies, hardened around the

contours of poses that those bodies assumed in a moment of despair

and death. It is something extreme and private, which gives us a direct

understanding of our body as a timeless shadow of suffering flesh –

something which maybe we should have been never able to see. In a

way, Archipenko told us that sculpture should be something radically

different, but what?

Young sculptors at the time agreed on a series of points. Elie

Nadelman, who exhibited with Archipenko in those years, used to say:

‘There is a plastic life and a life of living beings which are completely

different from each other’. Constantin Brancusi echoed him: ‘Look at

the ancient Greeks. When they depicted contortion and suffering in

their sculpture, that was the beginning of their decline’. The struggle

was to find a new style in sculpture, something capable of reuniting

two apparently irreconcilable elements. In the words of André Salmon,

these sculptors were ‘archaic and cutting edge’ at the same time. If

they were scrutinizing the entire catalogue of antique and primitive

styles, they did so in order to reconfigure their subject anew, through

a formal simplification that countered any remnants of naturalism. In

an essay devoted to Archipenko, the famous art critic and poet Guillaume

Apollinaire wrote: ‘The originality of Archipenko’s temperament does

not, at first glance, seem to reflect any influence at all from the art of

the past. Yet he has taken whatever he could from it; he realizes that

he is capable of going beyond it audaciously’. The sculptor’s engagement

with the past did not escape the press and the larger public. In a cartoon

by Georges Léonnec, published at the time of the 1912 Salon des

Indépendants, two ladies visit the galleries and stop in front of

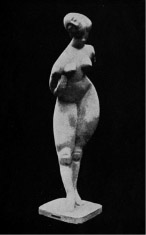

Archipenko’s Venus (fig.1).

Fig. 1 Alexander Archipenko, Venus, 1912

plaster, h. 198.1 cm, current location unknown, reproduced in Roland Schacht, Alexander Archipenko, Sturm Bilderbuch 2, Verlag Der Sturm, Berlin 1924

The first, puzzled by the reference to Antiquity, asks: ‘Really? Do

you think that she is the sister of the one at the Louvre?’ And her friend

responds: ‘Yes, but they are not from the same father’ portraits(fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Georges Léonnec, Cartoon featuring Archipenko’s Venus at the Salon des Indépendants

La vie parisienne, 30 March 1912

Archipenko’s

Venus, a work in white plaster, with her long triangular nose, curved

hips, thin waist, flat feet with elongated incisions to indicate the toes,

and conic small breasts, embodies both archaic and truly contemporary

aesthetic values. It calls to mind, in particular, the first attempts at

representing movement that we find in Greek archaic art, which had

been excavated and studied in the second part of the 19th century. We

find a similar formal solution, for example, in the Cycladic female

statuette donated to the Louvre in 1876. (fig. 3)

Fig. 3 Cycladic artist, Statuette, 2700–2300

BCE, marble © 1998 RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski

Venus’s large hips

and the round incisions that indicate the form of her knees derive instead

from the archaic kouroi of Greece, like the statue discovered in the

Temple of Apollo in Actium (now Punta, Greece) in 1864 that entered

the Parisian museum’s collection in 1874. But the entire figure of

Archipenko’s Venus is also twisting in a spiral, her bust leaning forward,

like her right leg, her head is bowing starkly to her right. Her pose has

a charming allure of modernity, almost mimicking the flirtatious stance

of the well-dressed ladies who, in Léonnec’s drawing, surround her at

the Salon. As in the case of her Cycladic cousins, the body of Archipenko’s

Venus is smooth, its outline cuts sharp, long, curves against the

background. Some years later the critic Roger Allard would identify in

Archipenko’s work ‘two combined sources of prestige’: ‘a modern culture

and a barbarous taste’. Writing of Cycladic sculpture, Edmond Pottier,

a few years earlier, had stressed the same confluence in taste between

the archaic and the modern: ‘This aesthetic taste that seeks in the

squeezing of the waistline[…] a very special kind of beauty, which shocks

and pleases our modern eye, used to more regular proportions’. In

other words, in the early 1900s, what was most radically archaic seemed

most in tune with the latest sensibility.

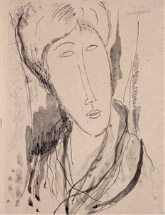

This confluence of faraway epochs and tastes, which informed

Archipenko’s primitivism, also fascinated a young Italian painter,

Amedeo Modigliani who, between 1911 and 1912, started working in

sculpture. In a series of preparatory drawings, we see the same Cycladic

details (wasp waist, round hips, circular breasts, long triangular nose).

Modigliani studied these features repeatedly. They went on to characterize

not only his later series of the Caryatids but even his portraits. (fig.4)

Fig. 4 Amedeo Modigliani, Head of a Woman

n. d., Ink and black wash on paper, 21 × 15 cm

Estorick Collection

At the same time, Modigliani’s drawings revealed

the influence that Art Nouveau illustrations had on his style: he used

a thick, assured line of contour. This line was the conceptual tool that

allowed him then to visualize his sculptures, proceeding from a two- to

a three-dimensional form. It was a line that was not concerned with

the environment: it securely cut out the smooth surface of his sculptures

from the stone. This linear quality was something that sculptors such

as Elie Nadelman, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Constantin Brancusi and

in particular Archipenko all strove for in those same years. It provided

a perfect bi-dimensional transition to their efforts to resurrect the

archaic technique of direct carving. Archipenko’s linear drawings

were often published in contemporary journals and exhibited along

with his sculptures. They reveal an incredible technical mastery and

allow us to comprehend not only the conceptual development of his

sculptures but also the way in which he saw bodies and forms in space.

Couple, for example, a pencil drawing created around 1911, shows the

elegant embrace of two figures, their bodies identified by a sequence of

smooth, curved sections. Like Venus, the fingers and toes are rendered

by simple linear incisions, the junctures of the body bulge as small

circles interrupting the evenness of the large surfaces.

Around this time, Archipenko, influenced by the Cubist painters,

progressively redefined his conception of space. The bodies of his

sculptures become more visibly composed of three-dimensional sections,

assuming a characteristic, faceted appearance. Still, in his work the

surface of the facets is often clean and well-defined, creating smooth,

rounded, angled sections interspersed with sharper, straight surfaces,

as in Draped Woman (1911) and Madonna of the Rocks.

Archipenko first created Madonna of the Rocks in plaster and painted

it red. The female figure has a certain Michelangelo-esque flare, with

the plastic pose of the legs and the dynamic torsion of the bust. It sits

on top of a cubic form, surrounded by soft, rounded elements intersected

by sharper ridges. These, along with the new Cubist group Family

Life, are works that the Futurist Umberto Boccioni probably saw in

Archipenko’s atelier when he visited it for the first time in June 1912

along with his friend and fellow Futurist Gino Severini.18 In February,

the Futurists had taken Paris by surprise with their group exhibition

of painting at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery. In the preface to the catalogue,

they had accused the Cubists of ‘doggedly stick[ing] to depicting the

immobile, the frozen, and the static aspects of nature […] we, on the

other hand, are searching for a style of movement that, before us, has

never been attempted’. They also sought to attain ‘the painting of the

states of mind’.

In the fall of 1912, Archipenko exhibited Family life at the Salon

d’Automne. Along with Modigliani’s sculpted heads, Archipenko’s

sculptures quickly became the most popular works of the show, as evidenced

by the critical attention they received as well as the frequency

with which they were reproduced in the periodicals of the time. (fig. 5)

Fig. 5 Article featuring illustrations of Archipenko’s and Modigliani’s works exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, in Comoedia illustré: journal artistique bi-mensuel, vol. 5, no. 2, 20 October 1912

However, French critics interpreted them according to a system of

values established by Cubist and Futurist painters. Archipenko had

already been called a ‘futurist’ back in March of the same year, just a

few weeks after the opening of the Futurist show in Paris. In his favourable

review of the Salon, Claude Roger-Marx read Archipenko’s

and Modigliani’s works as an ‘astonishing effort on the part of intelligence

to break its own laws [...] so as to know the unknowable and to

think the incomprehensible’, called Modigliani’s heads ‘Cubist’ and,

alluding to Archipenko’s dynamism, concluded: ‘Rodin will appear the

most calm of the masters after the statues of Archipenko’. The art

critic for Les Annales also used Futurist texts to make sense of

Archipenko’s sculptures. Not only did he explicitly call Archipenko a

‘futurist’, but he also heaped praise on one sculpture in particular that,

for him, represented ‘the state of mind of a family: the father, mother,

son and even the dog are merged into one single being’.

This confused reading of the Futurist theory concerning the representation

of ‘states of mind’ was not what attracted the Futurists to

Archipenko. They were instead impressed by the Ukrainian’s unabashed

use of colour and by his volumetric accentuation of the plastic form.

The simplification and movement of Porteuse (fig. 6) (exhibited in the

spring of 1912 at the Salon des Indépendants), together with the spiral

construction of works such as Madonna of the Rocks, offered a plastic

counterpart to the search for dynamism found in their own paintings.

Boccioni at that time was busy trying to translate his theories into

three-dimensional forms.

Fig. 6 Alexander Archipenko, Porteuse, 1912

stone, Private collection © 2011 Christie’s Images Limited

Contrary to Archipenko, he had no systematic

training in sculpture and had spent his entire career as a painter

and illustrator. He felt, however, that Futurism should expand into the

realm of sculpture. At the end of the summer of 1912, his Manifesto of

Futurist Sculpture started to spread in artistic circles. It listed a series

of radical ideas, which went against any accepted practice in the field

of sculpture. Boccioni called for the use of non-traditional materials in

sculpture by saying: ‘perceiving body parts as plastic zones, in a Futurist

sculptural composition, we’ll use wooden or metal planes, immobile or

mechanically mobile, in order to depict an object; hairy spherical forms

for the hair, glass semicircles for a vase; iron wires and grids to depict

an atmospheric plane’. The climate of expectation that this manifesto

generated was incredible. As soon as the Futurists announced that

in 1913 they would present a new exhibition of sculpture, every newspaper

started to speculate about these announced ‘dynamic’ artworks.

Probably following the path outlined by Boccioni, Archipenko, in 1912,

started to work on his first assembled and by all accounts ‘movable’

sculpture, portraying a female juggler from the Medrano circus. (fig. 7)

Fig. 7 Alexander Archipenko, Medrano, 1912

Illustration published in Enrico Prampolini’s journal Noi, vol. 1, nos 5-6-7, January 1919

The arm of the juggler, in fact, could be lifted up and down. In the

second part of 1912, Picasso and Braque also started to experiment with

paper and cardboard sculptures. When a year later Boccioni exhibited

his sculptures in Paris, he made large use of plaster as a way to keep

together a plurality of materials. However, he had not forgotten the

treatment of space in Madonna of the Rocks and Draped Woman,

which helped him go beyond his first understanding of Cubism. If we

observe his famous Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (fig. 8, 9),

for example, we see a series of long, conical elements emerging from

the undulating surface of the body: one on the left shoulder blade, another

in front of the head. In the front, the left side of the head is defined

by a hollow section of a cone. Its smooth surface is sharply stopped,

right over the shoulder.

Fig. 8, 9 Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913, bronze, cast 1950

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Similarly, the surface of the right shoulder

smoothly projects outward until it stops with a sharp edge. This is a

feature that he found in Archipenko’s sculptures of 1911–1912, where

the geometrization of large masses is generally treated with soft and

rounded edges until, as we saw, they are abruptly stopped with a clean

cut. Even the detail of the sharp ridge in the lower part of the Madonna

returns in Boccioni’s sculptures, for example, on the right thigh of

Unique Forms and at the level of the hip in the right-hand side of Spiral

Expansion of Muscles in Movement. Later, Archipenko himself would

expand on the effect created by the hollow section of a cone, visually

inverting empty and full spaces, as in Woman Standing, and Seated

Woman.

Already in 1911, Apollinaire had celebrated the world of the circus

writing: ‘I even admit that the short improvised sketches [...] in which

the acrobats of Medrano excel seem to me the only spectacle that’s

worth listening to and watching

these days’. Archipenko’s Medrano

I, a multi-material sculpture representing

a female juggler from the

Medrano circus, paradoxically

encapsulated more closely the

ideas of Boccioni’s 1912 Manifesto

of Futurist Sculpture than the

works that the Futurist himself

exhibited a year later. Besides

being partially movable, Medrano

I included ‘wooden and

metal planes’, tin sheet and glass,

and even ‘iron wires’, used to suggest

the curve of the right shoulder.

It was conceived in order to flaunt

its assembled nature. Like some ancient dolls or, better, like an artist’s

mannequin, its joints were enormous wooden balls. Structurally,

however, the sculpture was organized around a vertical axis, so that

the figure’s femur was planted in the middle of the calf, a detail that

further reinforces its anti-naturalistic appearance. Medrano I was not,

however, an illogical turning point in the artist’s production. Archipenko

often relied on his earlier, more naturalistic works as a structural

framework for conceiving a radically modern image. Medrano’s juggler

references his earlier Kneeeling Woman (c. 1910) and also

echoes a similar work that Archipenko’s friend from those years,

Wilhelm Lehmbruck, had successfully exhibited in Paris. The face is

rendered with a round sheet of metal, bent at the centre, upon which

the artist attached a long, thin wooden rectangle to indicate the nose.

He also painted the woman’s eye and mouth on the metal surface. These

procedures recall those used by archaic sculptors in their definition of

the face’s details, and which Archipenko echoed that same year for the

nose of the male figure in Family Life. Medrano’s conical breast and

large, extended foot, in the shape of a trucated cone, are further details

that return here from previous sculptures. Archipenko would retain

these features in the second version of the sculpture, featuring a ballerina

from the same circus, Medrano II (fig. 10).

Fig. 10 Alexander Archipenko, Medrano II, 1913–1914

painted tin, wood, glass, and painted oilcloth, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum New York

He conceived it the

following year, with a significant difference: this time it was mounted

against a flat, reddish background, establishing itself not as an autonomous

sculpture in space, but as a three-dimensional projection. A

drawing created at that time depicts a dancer’s pose in a similar way

and might have served as a study for the sculpture. Picasso’s

sculptures, illustrations of which first appeared in the fall of 1913, also

jut outward from a flat background, like collages that exit the frame to

enter into the space of the observer (fig. 11).

Fig. 11 Pablo Picasso, Guitar, 1912

paper, cardboard, string, painted wire, twine, tape, glue, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

As Christine Poggi has

shown, Picasso’s constructions destabilize the viewer, creating the

simultaneous impression that the work is two- and three-dimensional

at the same time. It is possible that the ballerina of Medrano II was

indeed some sort of ‘correction’ of the juggler of Medrano I, purged of

its Futurist characteristics and aligned with the new criterion of Cubist

sculpture that Apollinaire was outlining in 1913. Even the wooden

spherical joints are in fact flattened into mere painted circles. Seated

Figure, however, conceived in this period, reveals that Archipenko

did not completely shelve the model of Medrano I. Indeed, several of the

artist’s subsequent sculptures, like another Seated Figure, this time

from 1917, echo his earlier experiments with the Medrano constructions.

Some of his drawings even explicitly refer to them.

Archipenko would continue to develop his study of the relationship

between the body’s construction and the flat background in a mixed-media

work that is now destroyed, Woman in Front of a Mirror (fig. 12),

leading eventually to the development of sculpto-painting.

Fig. 12 Alexander Archipenko, Woman in Front of Mirror, 1914

Courtesy of The Archipenko Foundation

Compared to the two Medranos, this Woman’s head was conceived in a more

complex way, through a multiplicity of intersecting planar surfaces.

Eventually, Archipenko decided to turn the detail of the head conceived

at that time into an autonomous sculpture. Around 1913–1914,

Ardengo Soffici tackled the same theme in a style that followed more

closely the codes of analytic Cubism. He disassembled the

woman’s body, but still maintained a sculptural feeling: the muscular

masses of her back are large, curved sections. They are separated, but

the viewer can easily rejoin them in his mind, reconstituting the body.

It is at this time that Archipenko also moved away from the flat, wooden

silhouettes of his earlier constructions and the linear solutions of

his previous drawings. Now, his drawings and works on paper helped

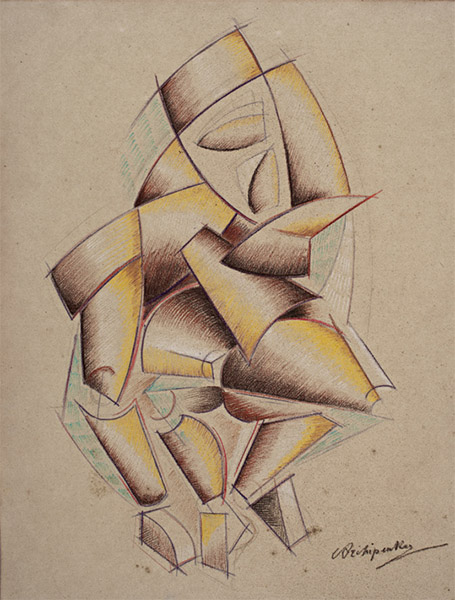

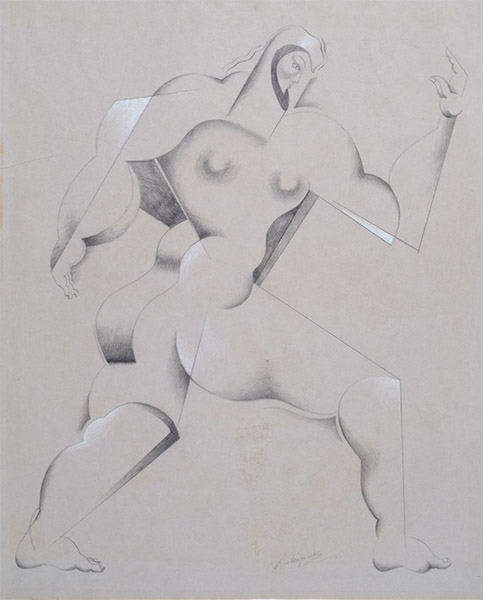

him redefine his volumetric effects. In works like, Figure in Movement

and Dancing, he constructed his figures by adjoining

conical elements, employing collage and a variety of pigments (pastel,

chalk) to better visualize the effect of the curved surfaces. As Gino

Severini had done with his ballerinas, Archipenko subdivided

the body into pliant conical shapes to suggest energy and movement.

Severini’s studies, along with Léger’s, influenced how Archipenko

reorganized the arrangement of the body parts. First he did so in his

drawings and then he conceptually transitioned the two dimensions of

the drawings into the three dimensions of the sculpto-paintings and

sculptures. We can retrace this process in his later sculpto-painting

Figure, realized in the 1950s, which reworked the model of a 1917 gouache.

At the same time, his heads started to be streamlined into an

ovoidal shape that will become iconic for him. More and more, his figures

embraced the essentiality of the atelier’s mannequin, while increasing

their impression of energy.

He further experimented with the dynamicisation of conical shapes

in plaster works such as Carrousel Pierrot (1913), Boxers (1913–1914)

and Gondolier (1914), which he showed at the 1914 Salon des Indépendants

together with Medrano II. Popular amusements such as the circus, the

fair and the boxing match were the ‘tangible miracles of contemporary

life’ that the Futurists had identified as the best source of inspiration

for modern artists. It is puzzling to see the multicoloured surface of

Carrousel Pierrot (fig.13), a work influenced by the dummies that

topped the carrousels and the carnival floats (fig. 14), but conceptually

tied to the study of balance and mass that Archipenko had addressed

already in Porteuse.

The French counterpart of Harlequin seems

to have stolen his famous costume. We do not know if Archipenko had

originally thought of maintaining the plaster’s white surface to keep

up with Pierrot’s more traditional white outfit. It is clear that the work

now relates more seamlessly (and spectacularly) to the corsets of the

Medrano sculptures and, like them, it features several juggling balls

positioned around the body. More complex in its structure, Gondolier (fig.15)

resolves plastically some of the problems of the first Medrano.

Fig. 13 Alexander Archipenko, Carrousel Pierrot, 1913

painted plaster, Solomon R. Guggenheim, Museum, New York

Fig. 14 Rol Photographic Agency, Third Thursday of Lent in Paris: The Float of Pataud, 1910

glass negative plate, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département Estampes et photographies, El-13 (70.2)

Fig. 15 Installation view, Venice Biennale 1920, Courtesy of The Archipenko Foundation

The triangular corset and the different planes that composed the skirt

of the ballerina are now elegantly rendered in a multifaceted hourglass

structure that twists around the central axis of the legs and the diagonal

of the oar. The shoulders are a rounded, moon-shaped element.

The same detail reappeared in Seated Figure, and later expanded

in the ovoidal flowing coat of his Walking Soldier. This

latter work also reveals a further step forward in the artist’s later reassessment

of the human body. The conical limbs are here replaced by

tubes, an element that also characterizes several of Archipenko’s

sculpto-paintings. It is a choice that scandalized the press both in Paris

and, later, at the Venice Biennale, because it seemed that Archipenko

used industrial, ready-made objects in his works, blurring the divide

between the artistic and the everyday. In Paris in 1914, critics insisted

that the gondolier’s oar was indeed a stovepipe and drew a connection

with a famous Dahomey sculpture in the Musée du Trocadero, which

was indeed constructed by assembling pre-existing objects (fig.16).

Fig. 16 Ekplékendo Akati, Statue of the God Gou, 1859–1889

iron, Pavillon des Sessions, Musée du Louvre

Boxers instead, could not be mistaken for an African assemblage:

it is a monochromatic, abstract composition in which the movements

of the two athletes define large and smooth interlaced energetic triangular

surfaces, similar o Boccioni and the Futurists’ later experiments

with coloured dynamism.

1914 was a capital year for Archipenko in Italy: Carrousel Pierrot,

Medrano II and Boxers were bought by the young Florentine artist

Alberto Magnelli for his uncle’s art collection. Magnelli was a friend

of the Futurist Carlo Carrà and Ardengo Soffici, who was then co-editor

of the Florentine avant-garde journal Lacerba. It is possible that

the decision to bring Archipenko’s most radical works to Italy was an

indirect attack on the part of the artists reunited around Lacerba

against Futurism’s leader, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and its most

visible sculptor, Boccioni. Archipenko published two drawings in

Lacerba that reveal his ability to merge simplification and dynamism.

He later transposed one of them, first, into a bronze high-relief and,

later, a coloured gouache. Carrà also planned for art

critic Roberto Longhi to write a monograph on Archipenko - a significant

move, since Longhi was at the time finishing a book on Boccioni’s

sculptures. Still, Archipenko maintained excellent relations with

Marinetti as well, and was invited to exhibit in Rome that same year

along with other artists recognized as ‘international’ Futurists.

Significantly, the Roman show did not feature any Cubist artists,

erasing a stylistic and theoretical confrontation that had become quite

heated in the years 1913–1914. Archipenko remained part of one of the

most important collections of modern art in Italy that allowed for this

comparison. Magnelli’s visitors in fact could enjoy ‘Macchiaioli and

Archipenko, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Carrà, etc.’

In his essay ‘Modern Life and Popular Art’, dated 15 March 1914,

Carrà clarified his position, writing: ‘Thank God Cubism is now dead

[…] In my opinion, the fundamental explanation for this artistic massacre

lies in the fact that all art which is constructed on intellectual

and cerebral foundations cannot last long. We Futurists are now

convinced that only by working the twofold mine of modern life and

popular art [will we be able] to create a modern primordialism’. Carrà’s

departure from Futurism during the period of the war did not cause

him to forget Archipenko. In 1913 he had devoted two drawings to two

kneeling figures of the circus: a circus ballerina and a trapeze artist.

Again, in 1914, he had sketched an acrobat with a semicircular head

that recalls that of Medrano. In 1917, however, as he was beginning

to define Metaphysical Painting, he returned repeatedly not to his own

works, but to the first version of Medrano. He created more than ten

drawings that, with minimal variations, repeat the theme of a kneeling

mannequin on a square platform, often accompanied by a putto or a

little angel (fig.17).

Fig. 17 Carlo Carrà, Mother and Child (Mannequin with Angel), 1917

pencil on paper Civico Gabinetto dei Disegni, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

The same mannequin returns, walking in an interior,

in another drawing dated 1918. Carrà used these drawings

to conceive his painting Mother and Child (1917), where, however, the

kneeling mannequin is morphed into a seamstress’s dummy. Covered

with sections of fabrics in different colours, the dummy’s bust recalls

another sculpture by Archipenko, Carrousel Pierrot, whose multicolour

corset reappears again in one of Carrà’s most iconic paintings of

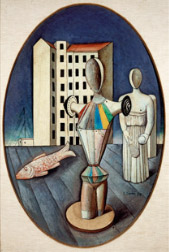

the time, The Oval of Apparitions (1918) (fig. 18). In the same vein,

Giorgio de Chirico would also produce several mannequins that flaunt

their artificiality, like Archipenko’s earlier constructed sculptures (fig. 19).

Fig. 18 Carlo Carrà, The Oval of Apparitions 1918

oil on canvas, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome

Fig. 19 Giorgio de Chirico, The One who Returns, 1918

oil on canvas, Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

In an essay published in the journal Valori Plastici (April – May

1919), de Chirico wrote: ‘Schopenhauer defines the insane as people

who have lost their memory. An ingenious definition. The logic of our

normal activities and lives is in fact a continuing band of memory of

the relationship between our environment and ourselves’. The artificiality

of the mannequin is uncomfortable because it is a betrayal of

the separation of these two realms: it is at the same time object and

person. In a paradoxical turn of events, when a year later Archipenko

exhibited at the Venice Biennale in the Russian Pavilion, critics interpreted

his sculpture in light of Metaphysical Painting, and of that world

of puppets and toys that characterized the work of Fortunato Depero

and Mario Sironi around that time. The influential sculptor

Antonio Maraini, for example, wrote: ‘If I had to classify Archipenko’s

sculpto-painting, I would put it between a prosthesis, an anatomical

model produced by Paravia, some tenpins, a rug with matchstick boxes,

etc. And this frees me from having to describe it’. Even his friend

Soffici interpreted Archipenko’s modern primitivism as a deliberate

attempt to embrace the practice of the humble muzhik, ‘who sculpts

and colours those peasant toys of the fairs of Novgorod and Kiev, which

are so naïvely beautiful, in their monstrous forms and shining and

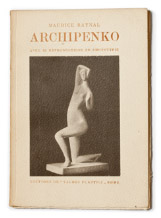

blaring colours’.41 When the editor of Valori Plastici decided to publish

an illustrated monograph of Archipenko’s work, however, the choice

fell not on Medrano or any work that Magnelli had bought, but on that

first version of Kneeling Woman which reunited a hieratic pose with

an elegant stylization (fig.20).

Fig. 20 Cover of Maurice Raynal’s monograph on Archipenko, featuring Kneeling Woman (c. 1910)

Edizioni di Valori Plastici, Rome 1923 © 2011 Christie’s Images Limited

The Futurists’ early christening of Archipenko as an international

member of their group in 1914 led to several unexpected outcomes in

the 1920s and 30s. First of all, they staged very visible and loud protests

when he was invited to exhibit at the Biennale. Marinetti wrote: ‘Inviting

foreign Futurists and excluding the works of the Italian Futurists like

Boccioni, Balla, Russolo, Funi, and Sironi is an ignoble and shameful

misdeed which does not deserve polemics, but kicks in the rear’. At

the same time, Archipenko proved essential for expanding the Futurists’

international connections after the war. He helped Enrico Prampolini

organize an exhibition of the Section d’Or in Rome in the early 1920s

and became one of the leading artists of the International House of

Artists led by the Futurist Ruggero Vasari in Berlin. It is in Prampolini’s

journal Noi that we find one of the few remaining illustrations of the

first version of Medrano and the friendship between the two is revealed

in a famous photograph by Bragaglia. Vasari also chose a work

by Archipenko for one of the ‘Futurist postcards’ that he printed in

conjunction with his journal Der Futurismus, and helped distribute

and advertise in Italy the monograph that Hans Hildebrandt devoted

to the sculptor in 1923.

But what is most astonishing is the impact that Archipenko had

on the development of Italian Futurist sculpture between the very late

1920s and the 1930s. It is an influence mediated first and foremost by

periodicals and books, given the fact that Archipenko did not exhibit

in Italy during that decade. His importance is nonetheless undeniable:

Futurist artist Regina Bracchi, for example, had only three books on

individual sculptors in her library. One was devoted to Michelangelo,

the others to Archipenko. The Futurist press in those years continued

to stress the centrality of Boccioni (who had died in 1916) for modern

sculpture, but it is easy to see the Ukrainian artist’s influence on the

movement’s younger sculptors. This owes to the fact that Archipenko

offered, throughout his career, a catalogue of disparate ways to visualize

the human body that were all equally groundbreaking. Like the

Futurists, he refused to treat the human figure as a mere reference to

canonical historical precedents, and this liberty, paradoxically, derived

exactly from his longtime meditation on archaic and primitive modes

of conceiving the body. For instance, his reassessment of the torso

resonates with the study of the human body that Prampolini

and Nicolay Diulgheroff were defining in those years. In

his paintings devoted to female subjects, Fillia used Archipenko’s

sculpto-paintings, transposing onto the canvas the sculptor’s use of

tubular elements. As Marzio Pinottini acutely reminds us, ‘if [Futurism]

wanted to champion an Italian art that could be truly universal, it could

not ignore the avant-garde movements’ of the time. This also applied

to Archipenko, who left his most lasting influence on Futurist sculpture.

We recognize it in particular in the treatment of the surfaces and the

choice of materials found in Thayaht’s works. As Fillia noted: ‘Thayaht

is aware of the hazard created by weight and by plastic matter, therefore

he tends to substitute volume with surface, transforming the latter into

a totalizing means of expression’.46 He conceived his Violinist

as a combination of smooth, flat curves that rise from a faceted base

and define the torsion of the body in large, vertical sections. It is a

solution that Archipenko had experimented with in the central, sinuous

element of Walking Soldier, which Thayaht probably had in mind.

Similarly, in Helmsman (a work that Thayaht conceived to be

painted), he reworked the harmonic interplay between smooth, curved

surfaces and sharp edges which Archipenko had mastered. Colour is

a distinctive feature of Archipenko’s works, and his 1930s sculptures

in terracotta and painted clay call to mind some of the contemporary

efforts of Lucio Fontana. It is Mino Rosso’s sculpture, however, that

reveals most strikingly Archipenko’s influence on Italian modern art.

His Mannequin and Skier closely reformulated the model offered

by Archipenko’s Gondolier, including the detail of the left arm

folding around the vertical axis of the standing body. His 1928 Feminine

Architecture echoed Archipenko’s famous inversion of hollow

and empty volumes in the treatment of the head. As Fillia

wrote, in his first sculptures, Rosso merged volumes of bodies and

atmosphere in an elastic (and here Fillia used a term that was crucial

for Boccioni’s theoretical development) ensemble. Later, Rosso’s group

sculptures, like Rugby Players and Boxer, still recalled

several of Archipenko’s features, such as his distinctive mannequins’

heads, the accumulation of masses and the large flat surfaces that

indicate the energy of the movement. They also revealed, however, a

distinctive treatment of volumes. As Pinottini points out, ‘the massive

quality of the blocks plays a crucial role, even if it is framed within the

inner workings of dynamism’. It is this dynamic element, the critic

clarifies, that constitutes one of the most significant links of Rosso’s

sculpture to the principles of Futurism; but his treatment of the

masses owes first and foremost to Archipenko's example.

Reassessing his long career in 1960, Archipenko remarked:

‘I find my name used by groups to which I never belonged, for instance

Dadaists and Futurists. In reality, I am alone and independent’. This

drive not only to engage with, but also to appropriate Archipenko’s work

was the result of the artist’s own success in establishing a new

working platform for future generations. As a veritable demiurge, he

was able to create a new catalogue of ways in which sculpture could

define itself as a modern enterprise, casting aside the shadows of both

Rodin and Pompeii.

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Madonna of the Rocks, 1911/1912 |

MINO ROSSO - Rugby Players, 1930 |

|

|

|

UMBERTO BOCCIONI - Study for ‘Empty and Full Abstracts of a Head’, 1912 |

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Head, 1913/1958 |

|

|

|

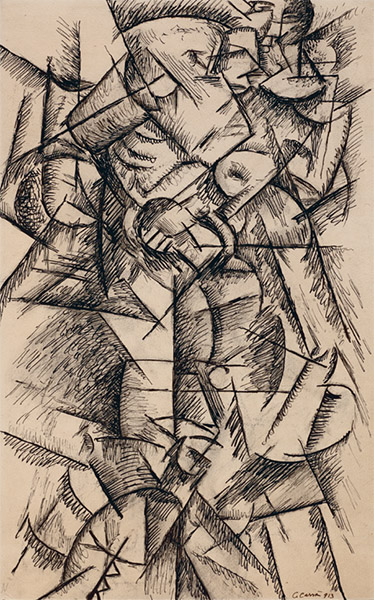

CARLO CARRÀ - Boxer, 1913 |

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Boxers, 1913/1914 |

|

|

|

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Title unknown [Dancing], 1914 ca. |

ROBERTO MARCELLO BALDESSARI - Dancer, 1915 |

|

|

|

GINO SEVERINI - Dancer (Ballerina + Sea), 1913 |

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Figure [version B], 1917/1921 |

|

|

|

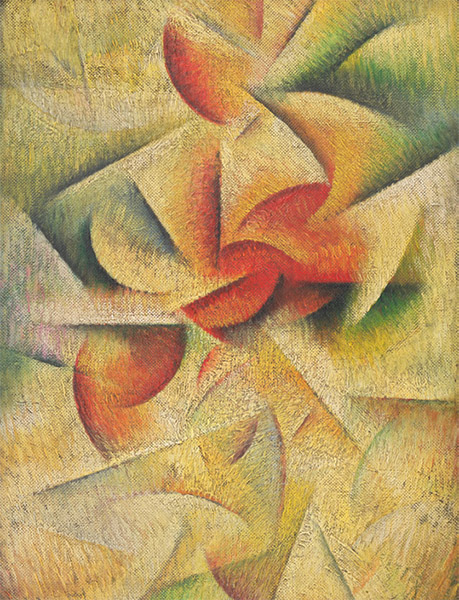

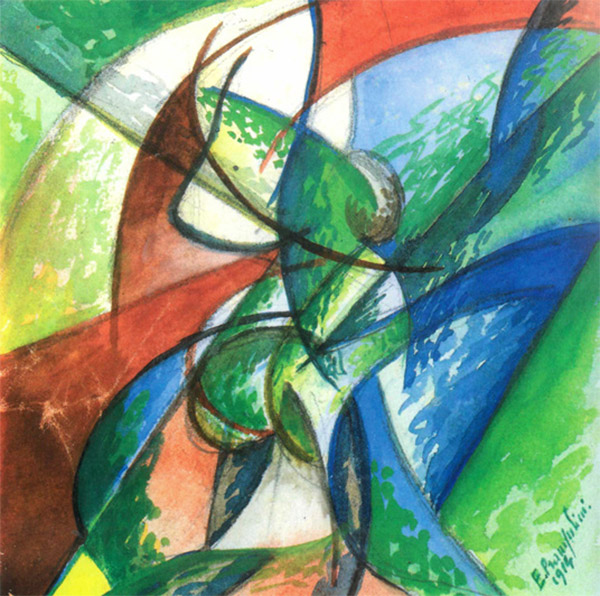

ENRICO PRAMPOLINI - Futurist Composition (Dynamism of Forms), 1914 |

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Form on Blue Background, 1913 |

|

|

|

MARIO SIRONI - Futurist City, 1914 |

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Title unknown [Walking], 1919 ca. |

|

|

|

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO - The Revolt of the Sage, 1916 |

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Architectural Figure, 1937/1957 |

|

|

|

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Woman Standing, 1916/1954 |

MINO ROSSO - Feminine Architecture, 1928 |

|

|

|

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO - Standing Woman and Still Life, 1919 |

FILLIA (Luigi Enrico Colombo) - Musician, 1928 |

|

|

|

NICOLAY DIULGHEROFF - Woman at a Window, 1927 |

FILLIA (Luigi Enrico Colombo) - Musician, 1928 |

Info Mostra

ARCHIPENKO and the Italian Avant Garde

London, 4 may - 4 september 2022

The event is free with an admission ticket purchased for the same day.

Tickets can be bought at the entrance or online